Mar 17

Celebrating Queer Memory in Our Cities

READ TIME: 6 MIN.

The following is reposted from The Conversation:

Ammar Azzouz, University of Oxford

Cities are like archives. Through their architecture, street names, monuments, plaques and cultural heritage sites, we learn about what remains of the past. But who is remembered in public spaces, and who is kept forgotten?

To diversify the histories revealed in these places, there are attempts around the world to give voice to hidden stories. This includes an increasing interest in representing the memory of LGBTQ communities, often absent from the public realm.

Think of the memorial to homosexuals persecuted under Nazism in Berlin, or the mural depicting the gay second world war code breaker Alan Turing in Manchester, and the statues of Virginia Woolf and Oscar Wilde in London, and even LGBTQ walking tours in cities like Athens, New York and Delhi.

As an architect and a researcher of cities, my work looks at how the past is represented through our social and built environment. I am interested in the stories told in our cities, as well as the stories untold. Most of all, I am keen to discover how to make our cities more inclusive, where different communities are represented, welcomed and safe.

Source: Ammar Azzouz/Author Provided

Telling LGBTQ Stories

In the UK, initiatives have emerged to archive, map and narrate stories of often oppressed and underrepresented communities. These vary in scope, from a bookshop, such as London's Gay's The Word, to posters on the underground representing LGBTQ communities, to entire neighbourhoods such as Manchester's Gay Village.

An excellent example of celebrating queer memory is the Pride of Place project by Historic England (an organisation that protects the country's heritage), which uncovers and celebrates places of LGBTQ history and contribution across England.

Stories of LGBTQ communities remain hidden in many cultures because of historical and continuing discrimination, criminalisation and violence. But efforts are made to bring these histories into the heart of cities. In 2022, a museum called Queer Britain opened in central London, making it the UK's first – and only – LGBTQ museum.

One way to celebrate and remember LGBTQ communities in cities is through street art and murals. In the heart of Brussels, for instance, the Out in The Street initiative brings a new narrative to the archive of the city.

A permanent 40-metre-wide fresco features stories of LGBTQ communities not only by celebrating the freedom they have, but also the difficulties and discrimination they face. A faceless migrant woman in a headscarf says: "You don't know me. You don't see me. I come from a country far away and I happen to love women. I'm proud of who I am. But I'm not ready to share my identity with you."

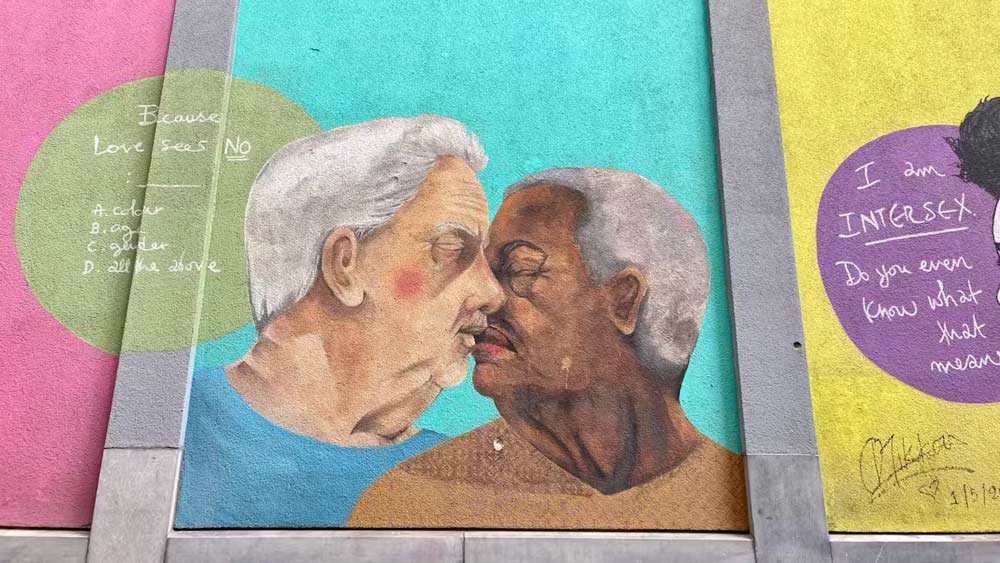

Elsewhere is a portrait of two elderly men kissing gently, eyes closed. The mural reads: "Because Love sees no: a) colour; b) age; c) gender; d) all of the above." Intersectionality seems to be at the heart of these portraits because there is a need to represent the richness of these communities and highlight the stories of "different" people such as Muslims, migrants and refugees.

Source: Ammar Azzouz/Author Provided

When Being Queer is Forbidden

Queer memory is commonly represented in big cities with rainbow flags, but this is often less visible in smaller places. Even so, many see rainbow flags as a shallow intervention that does not offer meaningful solidarity or support to LGBTQ communities.

In some places, its presence leads to danger. In Egypt, when activist and writer Sarah Hegazi raised a rainbow flag at a concert in 2017, she was arrested and tortured. Struggling with PTSD after her release, she fled to Canada where she ended her life in 2020.

In Brighton, a mural was painted in her memory citing a line from her suicide note: "To the world. You were cruel. But I forgive you." Hegazi's death led to global solidarity and she became a symbol of the LGBTQ struggle.

Afterwards, writer and activist Tareq Baconi reflected on living in the Arab region. In a piece titled, Our Lives are not Conditional, Baconi wrote: "Like other queers from the region, I am painfully familiar with the choice we all face at some point: conform or vanish... There was no sign of queerness around me... The persistent message is unwittingly or maliciously drummed into us: there is only one kind of normal."

Away from the queer capitals, LGBTQ communities navigate their towns and cities without the privilege of being publicly celebrated or acknowledged. In my research, published in 2019, I interviewed Syrians in exile about their stories of home and of their newly adopted countries. One man recalled a hammam he visited in Aleppo to meet with men, another remembered a bar and a garden in Damascus where gay men could gather.

A woman in Berlin told me that her life was a secret in Syria, a double life performed in public and private. "My home is the only place .. where I could hold her hand," she said.

Only a few minutes' walk from Out in the Street in Brussels, is another colourful mural of a smiling young man. We might assume it is a story of pride and celebration. But the mural – Love Remembers – is dedicated to the memory of 30-year-old Ihsane Jarfi killed in a homophobic attack in Belgium in 2012, and others like him killed in similar attacks there.

Celebrating queer memory within cities and towns reminds society of the achievements, the culture and the struggles of LGBT people. This is just part of the effort to bring other – often minority – stories to the fore, providing a fuller and more inclusive history of a place.![]()

Ammar Azzouz, British Academy Research Fellow, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.